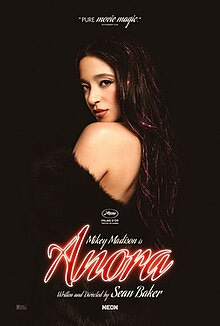

In Sean Baker's latest film Anora, we follow the journey of Ani, a sex worker navigating the complexities of her relationships, career, and identity. As a sex worker myself, the movie resonates with me on multiple levels. But beyond the personal connection, I find myself questioning the ethical representation of sex work and whether the film truly portrays the reality of this industry. My experience and perspective as a sex worker, alongside my reflections on the film, will explore how the movie both glamorizes and critiques sex work, while raising questions about who gets to tell these stories and for whom.

At the beginning of Anora, the portrayal of sex work is mostly glamorous: Ani, a stripper and escort, is seen performing her job with flair and confidence. She works in an upscale club, surrounded by attractive colleagues and clients. There’s a sense of excitement, luxury, and excess—private jets, high-end dinners, cocaine, and flashy spending. The glamorization is seductive, presenting a dreamlike version of the life many may envision when they think of sex work. But as the film progresses, the reality sets in, and this glamorization begins to fade.

By the end of the movie, the glamorized image fades, revealing the harsh undercurrents of power and exploitation in the world of sex work. While Ani enjoys autonomy in some ways, she is also caught in a larger power structure that commodifies her body and emotions. Anora exposes how sex work is a transaction, but it also illustrates the emotional toll that comes with this transaction. For many sex workers, the idea of intimacy can blur with fantasy, but it is never quite real. This contrast between autonomy and exploitation is central to the narrative, and it spoke to my own experience.

While Anora presents a compelling story, it is important to consider who is represented. The film centers on a white, cisgender woman, and while her experience resonates with me, it doesn't reflect the full spectrum of sex workers' identities. As a sex worker myself, I’ve often felt the need to represent my experience, which is far from universal. The demographics of sex workers, especially those in marginalized communities, are often ignored or underrepresented in mainstream media. In Anora, the world of sex work seems predominantly white, and the film doesn’t delve much into the racial or systemic issues within the industry, which is a missed opportunity. But also is that Sean Baker’s story to tell?

As a cis white woman provider with pretty fucked up notions of love, I saw myself reflected in Ani's character. Anora speaks to the autonomy that sex work can provide, but it also highlights how this autonomy exists within a system that often dehumanizes us. For me, sex work can be an act of empowerment—mostly being able to choose your clients, your hours, and your life—but it's also something that society defiles. The emotional dissonance of feeling both powerful and degraded is something I recognize deeply in my own work.

One aspect of Anora that particularly resonates with me is how the movie touches on the emotional complexities of being a sex worker. Ani's relationship with her client Vanya becomes more than transactional as time goes on; she becomes emotionally involved. I've had similar experiences. Many of us try to maintain boundaries, but sometimes, emotions get entangled in ways that make us question our own feelings and desires. There is often an underlying tension between wanting to preserve professionalism and the deep, human desire for connection. While the movie presents Ani as someone caught between worlds, I see her as a reflection of the contradictions I live with everyday and therefore why I feel seen in the movie.

The film’s portrayal of Ani's relationship with her client-turned-husband illustrates one way of how a provider might navigate romantic relationships, especially when marriage or commitment is involved. I’ve known a plethora of providers and I’ve summed up three scenarios based on different provider philosophy according to the rigidity of their boundaries.

Version One (rigid): Ani laughs off the proposal. Their relationship stays transactional.

Version Two (less rigid): Ani accepts the proposal, they get married but she’s only invested for the money so when the shit hits the fan with the family, she’s not broken up over it nor does she expect him to stay with her.

Version Three/Movie Version (porous): Ani accepts the proposal, they get married and when shit hits the fan, she expects him to stay with her and she’s heartbroken when he doesn’t. I mean this doesn’t do justice to the entire plot but you get the idea.

As a sex worker, I’ve experienced all of these emotions myself—sometimes I have deep feelings for clients. Sometimes, I even imagine a future with them. When consistently I see a nice, attractive regular with similar interests to me, it is often difficult to separate fantasy from reality. Both parties are presenting fantasies- client and provider. And sometimes I get really drawn to the fantasy that a client has presented themselves to be. Some providers have been disgusted when I’ve talked to them about my feelings for clients. Others have related. We’re all different. Ani’s story represents a worker similar to me whose romantic feelings can be swept up into the work but this characteristic is definitely not shared among all providers.

One of the central issues with Anora is the question of who gets to tell the story of sex work. While the film does a good job portraying the emotional complexity of Ani's character, it still falls short in truly representing the variety of experiences in the sex work industry. Sean Baker, as a director and writer, isn’t a sex worker himself, and the film is still shaped by his vision and the experiences of those who create it, not by the lived experiences of sex workers. It’s a delicate balance—one that needs constant awareness. I don’t expect mainstream movies to do full justice to any marginalized community, but I do expect more honest and nuanced portrayals of sex workers that go beyond stereotypes.

Despite its flaws, I found myself moved by Anora. The film spoke to my own experiences as a sex worker in ways that few mainstream films about sex work do. While it may not represent all sex workers, the emotional truths it touched for me were rattling. The glamorization, the emotional complexity, and the harsh realities of sex work are real and I think the film sheds light on these things when movies about sex workers usually don’t.

I walked out of the theater feeling proud of what I do, and for me, that’s a rare experience. However, we must continue to pressure mainstream media to tell stories about sex workers—accurately, ethically, and from our perspective—not from the lens of those who have not lived our experiences.

I will say that I like Sean Baker and very much appreciate his vision for telling stories of sex workers in an attempt to challenge stigma. In fact, the past three of his films are centered around sex workers. Anora won big at Cannes and Baker dedicated the award to all sex workers.

In conclusion, Anora is hot and you should see it.

Here is Sean Baker's q&a on Anora after winning Palme d’or and why he dedicated his award to swers.